So you are a multitasker. SMSing, what’s-apping or whatever while you check your email while typing on that document you really have to finish today, or studying for an exam. But it’s all fine, because you are a multitasker. Duh.

Better think that over again.

Consider the work of Ophir, Nass, and Wagner (2009) in the prestigious journal PNAS. Using well-established performance tests from cognitive psychology, they compared “heavy media multitaskers,” that is, people used to work with lots of distractions, with “light” ones. The result? Heavy multitaskers think they are more productive. But they are completely wrong: they are actually less productive.

Is this surprising? Of course not.

What is surprising is that a whole generation has grown up thinking that multitasking and reduced attention spans can substitute for concentration and depth of knowledge. It can’t.

To see why, let us consider a well-known phenomenon from psychology: the Perceptual Refractory Period.

Suppose that you are given some simple tasks. Cognitive psychologists use tasks which sound silly but which are the minimal units of cognition. For instance, you see a set of letters on the screen and have to decide whether it is an actual word or just a nonsensical string of letters. If it is a word, you push a button. If not, you push another.

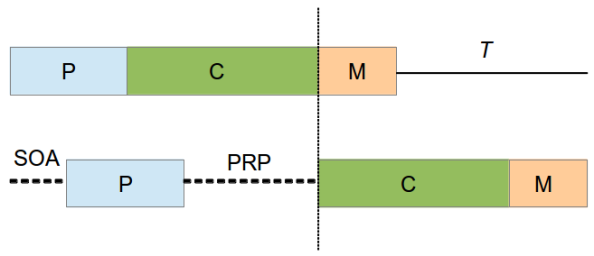

We know an awful lot about such tasks. As current theories go, what your brain does when facing such a task can be divided in three phases. In the Perceptual phase (P), you just see the stuff. In the Central processing phase (C), you do the actual thinking, classifying, and deciding. In the Motor phase (M), you implement the action, i.e. push a button.

It turns out that we can do a lot of P and M simultaneously, but we cannot do two different Cs at once. If you are busy with one C phase and another task reaches the stage where it calls for C, it will have to wait. The part of your mind which does the actual thinking can only take one C task at a time. Psychologists call it “the mind’s bottleneck.” Bummer.

How do they know that? The mind’s bottleneck was first described by Pashler (1992), and a lot of evidence has been collected since then. For instance, a more recent article by Lee and Chabris (2013) looks at individual differences in the bottleneck and explains the situation quite clearly. The key is the so-called Perceptual Refractory Period, or PRP. Look at this figure.

The upper line represents a task you are given, and the boxes illustrate what your brain does. P, then C, then M. Fine. However, the lower line represents a second task that you are also given before you are done with the first. These nasty experiments are an example of so-called dual task paradigms. In our case, a second string of letters appears on screen. The thing is, it appears with a slight delay, called the Stimulus Onset Asynchrony or SOA (gotta love their abbreviations, right?). Well, when the second stimulus shows up, you are happily engaged in P for the first task, so you readily multitask and start P for the second task too. But because of the SOA, before the second P is ready, you are already in the central, thinking stage C for the first task. Then P for the second task ends, and your brain needs to switch to C for that task too. But no can do: there is already one C running, and hence the second C waits until the first is completed. The time the task spends waiting for the other C stage to be completed is the PRP. Once the mind’s bottleneck is free again, the second C starts and runs in parallel with the motor stage M for the first task. In the end, of course, you complete the first task before the second task, and that difference in response times can be measured. Let’s call it T.

Now, what cognitive psychologists will do is make your life slightly harder in the second task. Maybe the chain of letters has a worse contrast and it is more difficult to read. Well, that means that you are going to take longer in the second task, hence the time difference T should be larger now, right? That can be measured in the lab. The effect? Nothing. Zilch. Zero. Nada.

Why is that? Look at the figure again. Well, since the letters are more difficult to read, the Perceptual stage is going to take longer. In the figure, imagine that the P of the second task gets larger. But that is not a problem: it can run in parallel to the C stage of the first task. It just expands into the slack provided by the PRP. The second C stage then starts exactly at the same point as it did before, and there is no change in T!

What the PRP and the mind’s bottleneck really mean is that, when we think we are doing two cognitive tasks at once, actually we are probably switching back and forth between them, never really concentrating in either one, and hence making a lot of mistakes without even realizing it. So much for multitasking. If you believe that you are multitasking, you are probably just wasting your energy on several tasks at once and being less effective than if you would just concentrate on one, finish it, then switch to the other. You are multi-wasting your time and effort, you will multi-fail, and you will become multi-frustrated.

So, if you have something important to do, close the email program, shut down your smartphone (or at least do not answer the what’s-thingies right away), put aside everything else, and, incidentally, if you need to listen to music, it is probably better to settle for instrumental and avoid your language centers getting involved in more than one task at once (but that’s a story for another day…).

NOTE: This post first appeared in 2014 in my university blog. Since I have taken down that one (one person, one blog seems more than enough to me), I am re-posting here slightly updated versions of some of the posts which used to be there.